![]() This content is brought to you by the Association for Christians in Student Development (ACSD), an organization committed to equipping and challenging faithful professionals to infuse their Christian faith into student development practice and scholarship. Interested in becoming a member for more awesome content just like this? Join today by clicking here!

This content is brought to you by the Association for Christians in Student Development (ACSD), an organization committed to equipping and challenging faithful professionals to infuse their Christian faith into student development practice and scholarship. Interested in becoming a member for more awesome content just like this? Join today by clicking here!

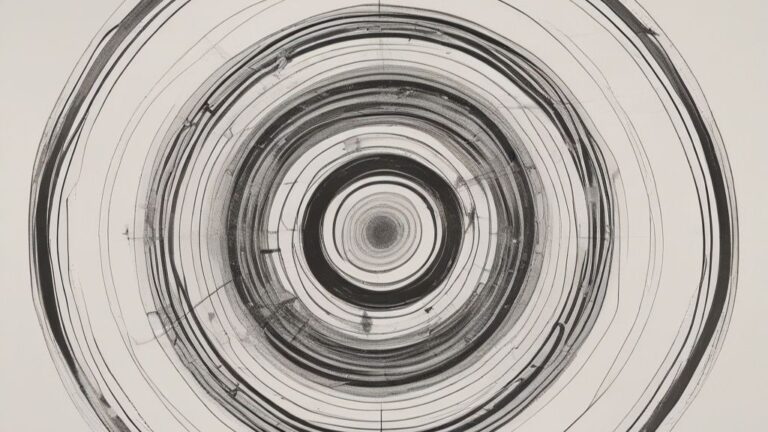

The work of higher education is inherently cyclical in nature. Every year, a new group of students join our institutions and other students leave, having completed their time being formed by (and forming) those communities. Each student brings their own deeply-embedded perspectives, values, and goals with them as their life converges with the institutional community like a tributary flowing into a river. Much like the swirling water at the confluence of tributaries and rivers, the waters of Christian higher education can be similarly tricky to navigate as both institution and student must determine how to prepare well for the moments of dissonance that can result in that merger.

As co-curricular educators, we stand in the confluence. It is our work to engage in the formation of mind and character of our students, which requires patience and persistence for the long process of life change through the “two steps forward, one step back” approach that many (if not all) of our students experience during their journey. Given this dynamic, it is helpful to consider developing our communities through the lens of being centered and not bounded sets, to borrow from the field of mathematics, as we draw students into the compelling central goal of becoming more like Christ and participating in his redemptive work on earth.

First, a few definitions. A bounded-set is, at its most basic level, a static group of like-items or objects around which is a clearly defined boundary (Baker, 2022). Each of those items and objects (or in our case, people) must adhere to a specific set of criteria to belong within the defined boundary. If they do not, then they are not in the set at all. A pear, an apple, and an orange are all clearly within the set of fruit while a paperclip is clearly not.

A centered-set, on the other hand, is a dynamic set; it is less about the criteria that define the edges and more about the criteria that defines the compelling element at the center of the set (Baker, 2022). Each item or object (or again, in our case, person) is evaluated by two criteria relative to the center of that set: (1) the direction it is moving (either towards or away from the center), and (2) the speed at which it is moving (either fast or slow). Someone choosing to eat a balanced diet and participate in physical exercise is taking steps towards being healthy, but they are not either healthy or not healthy, because healthy is not a clearly defined set that one can be in.

I would suggest that the work of character formation and discipleship requires us to be comfortable with centered-set thinking. In Christian higher education, we would do well to consider how we are forming communities that are ready to form students who are daily moving towards and away from Christ-likeness. This is the work; too often we forget that our job is student development and instead expect students to be finished products immediately. We often develop (or inherit) student conduct policies that reflect a bounded-set mindset whereby belonging in the community is defined by “tests of orthodoxy (right beliefs) or orthopraxy (right practice) or both” (Hiebert, 1978, p. 26). This is not to say that either of those are wrong to value or pursue; indeed, both have an incredibly valuable role in forming the compelling center of our centered-set communities. Instead, we must be intentional about the way we engage with students as they take “two steps forward, one step back” during their journey with us, recognizing that “the growth toward the center of the set is the same as the process of discipleship” (Braught, 2013).

“In Christian higher education, we would do well to consider how we are forming communities that are ready to form students who are daily moving towards and away from Christ-likeness.”

Thankfully, we often see great examples of student development practitioners working through a redemptive discipline framework instead of a “one strike and you’re out” mindset for student conduct, but the pressure and temptation are ever-present to rely on bounded-set thinking. Pressure can come from well-meaning and insistent parents, alumni, donors, leadership, and even students who are concerned about whether an institution is supporting its Christian identity faithfully when seemingly allowing community members latitude in their conduct. Temptation can come from the desire to preserve the community we are cultivating or to have something concrete to help us address a tricky situation instead of wading into the murky water of nuance that often feels a bit unsettling.

Dissonance is, by definition, a form of tension and we tend to not always appreciate tension readily.

However, within limits, a healthy amount of dissonance can be a valuable source of collaborative growth for both the individual and the community. We are comfortable with the phrase “iron sharpens iron” (Proverbs 27:17) as an inspiring image of relational maturation, but can quickly forget that the process necessarily involves sparks. Greg Robinson suggests that the ulterior motive of shared alignment of beliefs and actions can have an unintended consequence within communities with a rich culture by marginalizing “those who are outside the defined norm of that specific [community]” or driving them out entirely. The result, he says, is that “the [community] works against the maturing of the members” because they do not participate in the formational opportunities of the community openly or honestly (Robinson, 2009, p. 20). If we do not create space in a centered community to navigate differences with the trust that one’s sincere desire to move closer to the center allows them the freedom to be candid about their deeply embedded perspectives, values, and beliefs that are dissonant with the institution, we will never move beyond what M. Scott Peck refers to as pseudo-community because the veneer of spiritual superficiality will forbid it (Peck, 1998). We may never have the chance to help the student resolve the tension of that dissonance.

Every faith-based institution has a unique mission that informs its strategies, hiring practices, behavioral expectations, and enrollment requirements, many of which are outside the control of student development practitioners to influence or change. Regardless of these elements, however, every institution will have within its community countless opportunities to participate in the formation of the community members if they have the fortitude to engage in the work of cultivating the patience for a centered-set community with a compelling core of participating in God’s redemptive work on earth with him. Many of our students come to campus, compelled towards our shared center, but sense or encounter boundaries that keep us from engaging with them in forming a true community where they can navigate with us the important matters in pursuit of clarity. We only get a few years with them before they head into the communities God is calling them into next, so I say let’s give them that opportunity while we can.

References

- Baker, M. D. (2022). Centered set church: Discipleship and community without judgmentalism. IVP Academic.

- Braught, R. (2013). Bounded set vs. centered set thinking. Veritas Church. https://veritas.community/veritas-community/2013/03/13/bounded-set-vs-centered-set-thinking

- Hiebert, P. G. (1978). Conversion, culture and cognitive categories. Gospel in Context, 1(4), 24–29.

- Peck, M. S. (1998). The different drum: Community making and peace. Touchstone.

- Robinson, G. (2009). Adventure and the way of Jesus: An experiential approach to spiritual formation. Wood n Barnes.